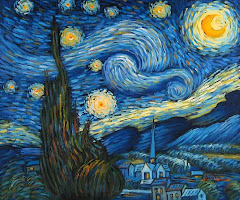

He who looks deeply and with a seeing eye into the poetry of yesterday finds there all the cold scientific magic of today and much which we shall not enjoy until some tomorrow. If the poet does not dream so clearly that blueprints of this vision can immediately be drawn and the practical conversions immediately effected, he must not for that reason be smiled upon as merely the mental host for a sort of harmless madness.My Dream

by Christina Rossetti

Hear now a curious dream I dreamed last night,

Each word whereof is weighed and sifted truth.

I stood beside Euphrates while it swelled

Like overflowing Jordan in its youth:

It waxed and coloured sensibly to sight,

Till out of myriad pregnant waves there welled

Young crocodiles, a gaunt blunt-featured crew,

Fresh-hatched perhaps and daubed with birthday dew.

The rest if I should tell, I fear my friend,

My closest friend would deem the facts untrue;

And therefore it were wisely left untold.

Yet if you will, why, hear it to the end.

Each crocodile was girt with massive gold

And polished stones that with their wearers grew:

But one there was who waxed beyond the rest,

Wore kinglier girdle and a kingly crown,

Whilst crowns and orbs and sceptres starred his breast.

All gleamed compact and green with scale on scale,

But special burnishment adorned his mail

And special terror weighed upon his frown;

His punier brethren quaked before his tail,

Broad as a rafter, potent as a flail.

So he grew lord and master of his kin:

But who shall tell the tale of all their woes?

An execrable appetite arose,

He battened on them, crunched, and sucked them in.

He knew no law, he feared no binding law,

But ground them with inexorable jaw:

The luscious fat distilled upon his chin,

Exuded from his nostrils and his eyes,

While still like a hungry death he fed his maw;

Till every minor crocodile being dead

And buried too, himself gorged to the full,

He slept with breath oppressed and unstrung claw.

Oh marvel passing strange which next I saw:

In sleep he dwindled to the common size,

And all the empire faded from his coat.

Then from far off a winged vessel came,

Swift as a swallow, subtle as a flame:

I know not what it bore of freight or host,

But white it was as an avenging ghost.

It levelled strong Euphrates in its course;

Supreme yet weightless as an idle mote

It seemed to tame the waters without force

Till not a murmur swelled or billow beat:

Lo, as the purple shadow swept the sands,

The prudent crocodile rose on his feet

And shed appropriate tears and wrung his hands.

What can it mean? you ask. I answer not

For meaning, but myself must echo, What?

And tell it as I saw it on the spot.

"The other day we heard someone smilingly refer to poets as dreamers. Now, it is accurate to refer to poets as dreamers, but it is not discerning to infer, as this person did, that the dreams of poets have no practical value beyond the realm of literary diversion. The truth is that poets are just as practical as people who build bridges or look into microscopes ; and just as close to reality and truth. Where they differ from the logician and the scientist is in the temporal sense alone ; they are ahead of their time, whereas logicians and scientists are abreast of their time. We must not be so superficial that we fail to discern the practicableness of dreams.

Dreams are the sunrise streamers heralding a new day of scientific progress, another forward surge. Every forward step man takes in any field of life, is first taken along the dreamy paths of imagination. Robert Fulton did not discover his steamboat with full steam up, straining at a hawser at some Hudson River dock; first he dreamed the steamboat, he and other dreamers, and then scientific wisdom converted a picture in the mind into a reality of steel and wood. The automobile was not dug out of the ground like a nugget of gold ; first men dreamed the automobile and afterward, long afterward, the practical minded engineers caught up with what had been created by winging fantasy.

For the poet, like the engineer, is a specialist. His being, tuned to the life of tomorrow, cannot be turned simultaneously to the life of today. To the scientist he says, "Here, I give you a flash of the future." The wise scientist thanks him, and takes that flash of the future and makes it over into a fibre of today."

Sources:

Commentary: By Glenn Falls

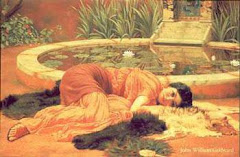

Art Photos by Florence Harrison