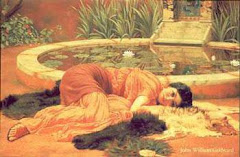

"The undisputable genius and greatest writer of the three Bronte sisters was Emily Bronte. She published only one novel, WUTHERING HEIGHTS, under the pseudonym of Ellis Bell. Wuthering Heights is the story of doomed love and revenge. Her novel was widely criticized by the Victorian critics for being so rustic and savage. As a young reader, I was enthralled by this novel even until now. Emily Bronte will always be on top of my list as a genius writer combined with her talent for mysticism and the spiritual." (Ophelia)

The moors that Emily Bronte described in Wuthering Heights

The moors that Emily Bronte described in Wuthering Heights "It is not simply in contrast to its origins that Wuthering Heights strikes us as so unique, so unanticipated. This great novel, though not inordinately long, and, contrary to general assumption, not inordinately complicated, manages to be a number of things: a romance that brilliantly challenges the basic presumptions of the "romantic"; a "gothic" that evolves—with an absolutely inevitable grace—into its temperamental opposite; a parable of innocence and loss, and childhood's necessary defeat; and a work of consummate skill on its primary level, that is, the level of language.

Top Withens believed to be the setting of Wuthering Heights

Top Withens believed to be the setting of Wuthering Heights Wuthering Heights is erected upon not only the accumulated tensions and part-formed characters of adolescent fantasy (adumbrated in the Gondal sagas) but upon the very theme of adolescent, or even childish, or infantile, fantasy. In the famous and unfailingly moving early scene in which Catherine Earnshaw tries to get into Lockwood's chamber (more specifically her old oak-paneled bed, in which, nearly a quarter of a century earlier, she and the child Heathcliff customarily slept together), it is significant that she identifies herself as Catherine Linton though she is in fact a child; and that she informs Lockwood that she had lost her way on the moor, for twenty years.

Top Withens from the South

As Catherine Linton, married, and even pregnant, she has never been anything other than a child: this is the pathos of her situation, and not the fact that she wrongly, or even rightly, chose to marry Edgar Linton over Heathcliff. Brontë's emotions are clearly caught up with these child's predilections, as the evidence of her poetry reveals, but the greatness of her genius as a novelist allows her a magnanimity, an imaginative elasticity, that challenges the very premises (which aspire to philosophical detachment) of the Romantic exaltation of the child and childhood's innocence.

Top Withens from the North

Top Withens from the NorthSo famous are certain speeches in Wuthering Heights proclaiming Catherine's bond with Heathcliff ("Nelly, I am Heathcliff—he's always, always in my mind"), and Heathcliff's with Catherine (Oh, God! it is unutterable! I cannot live without my life! I cannot live without my soul!") that they scarcely require reference, at any length: the peculiarity in the lovers' feeling for each other being their intense and unshakable identification, which is an identification with the moors, and with Nature itself, that seems to preclude any human, let alone sexual" bond. They do not behave like adulterous lovers, but speak freely of their relationship before Catherine's husband, Edgar; and they embrace, desperately and fatally, in the presence of the ubiquitous and somewhat voyeuristic Mrs. Dean.

Approach to Top Withens

Top Withens in 1920's

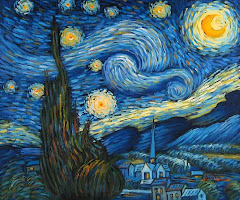

"Realism," the artfully fractured chronology begins to sort itself out, as if we are waking rapidly from a dream, and the present time of September 1802 is the authentic present, for both the diarist Lockwood and the inhabitants of Wuthering Heights. Mysteries are gradually dispelled; we have gained a more certain footing; as Lockwood makes his way to the Heights, he notes that "all that remained of day was a beamless, amber light along the west; but I could see every pebble on the path, and every blade of grass by that splendid moon." The shift from the gothic sensibility has been prepared from the very first, by Brontë's systematically detailed settings, which are rendered in careful prose by the narrators Lockwood and Mrs. Dean—the only characters we might reasonably expect to see the Heights, the Grange, and the moors. The romantic lovers consume themselves in feeling; they feel deeply enough but their feeling relates only to themselves, and excludes the rest of the world. But the narrators, and, through them, the reader, are privileged to see. (It is significant that the ghost-lovers of the older generation walk the moors on rainy nights, and that the lovers of the new generation walk by moonlight.)

It is this fidelity to the observed physical world, and Brontë's own inward applause, that makes the metamorphosis of the dark tale into its opposite so plausible, as well as so ceremonially appropriate. Though the grave is misjudged by certain persons as a place of fulfillment, the world is not after all phantasmal: it is by daylight that love survives. Long misread as a poetic and metaphysical work given a sort of sickly, fevered radiance by way of the "narrowness" of Emily Brontë's imagination, Wuthering Heights can be more accurately be seen as a work of mature and astonishing magnitude. The poetic and the "prosaic" are in exquisite harmony; the metaphysical is balanced by the physical. An anomaly, a sport, a freak in its own time, it can be seen by us, in ours, as brilliantly of that time—and contemporaneous with our own.

Wuthering Heights, as if for the first time in human history, that one generation will not be doomed to repeat the tragic errors of its parents. Suddenly, childhood is past; it retreats to a darkly romantic and altogether poignant legend, a "fiction" of surpassing beauty but belonging to a remote time.

Have blessed days ahead Bloggers!

Yours Truly,

Ophelia

Source: The Magnanimity of Wuthering Heights by Joyce Carol Oates

No comments:

Post a Comment